How Brands are Making Real Money Selling Virtual Goods

At first glance it can seem almost too good to be true. Products that offer infinite scalability with minimal overhead, that can move from concept to market in a matter of days without the hassle of manufacturing or distribution.

And yet this is exactly the kind of real-world, money-making opportunity available to brands willing to enter the bold new arena of virtual merchandise.

An Untapped Market for Brands

Over the last decade, the sale of virtual goods has exploded alongside the exponential growth of social media and gaming. The result is a multi-billion-dollar marketplace for products that, technically speaking, aren’t real. The money, however, is very real, with recent estimates putting the annual revenue of virtual products at more than $15 billion. Virtual goods can be anything from digital stickers for use in messaging apps to outfits for your avatar to extra lives in a digital game.

This entirely new product category has come about as part of the move to a “freemium economy” where consumers expect to get the services they want – everything from news to a mobile game – for free. Companies still have to pay the bills though, and so they’ve gotten creative in terms of monetization. The traditional approach has relied on advertising, but for many digital companies, in-app purchases of virtual goods offer a new way to keep the lights on while actually enhancing the user experience.

This entirely new product category has come about as part of the move to a “freemium economy” where consumers expect to get the services they want – everything from news to a mobile game – for free. Companies still have to pay the bills though, and so they’ve gotten creative in terms of monetization. The traditional approach has relied on advertising, but for many digital companies, in-app purchases of virtual goods offer a new way to keep the lights on while actually enhancing the user experience.

And people are very willing to spend their real-world money on these digital upgrades, sometimes a lot of it. The first-person shooter game “CS:GO” is notorious for its high-end virtual goods market, which sells a vast range of decorative virtual weapons (called “skins”) for upwards of $50,000. And that’s not even close to the biggest purchase ever recorded. In 2010, someone shelled out $635,000 for a virtual night club called Neverdie in the game “Entropia Universe.”

And people are very willing to spend their real-world money on these digital upgrades, sometimes a lot of it. The first-person shooter game “CS:GO” is notorious for its high-end virtual goods market, which sells a vast range of decorative virtual weapons (called “skins”) for upwards of $50,000. And that’s not even close to the biggest purchase ever recorded. In 2010, someone shelled out $635,000 for a virtual night club called Neverdie in the game “Entropia Universe.”

Of course, these kinds of big ticket sales are rare, just as they are in the real world, and most virtual goods price in under the $10 mark.

Activision Blizzard’s “Candy Crush Saga” continues to be the No. 1 top-grossing mobile game in the world five years after its initial release, thanks in large part to in-app purchases of its much more reasonably priced virtual goods. That doesn’t mean there isn’t money being made though – consumers spent $250 million on “Candy Crush” extra moves, color bombs and lollipop hammers in the third quarter of 2017 alone.

Now think about this – most of the products for sale in “Candy Crush” are native to the game, meaning they aren’t associated with any outside brand. But why couldn’t the lollipop hammer be made from a Chupa Chups or the color bombs be inspired by Crayola hues?

“People spend their money where they spend their time, and more and more people are spending their time in digital ecosystems, but brands aren’t fully capitalizing on this yet,” said David Uy, co-founder and CEO of BLMP Licensing Marketplace, a new platform that helps facilitate licensing partnerships between brands and digital publishers. “The digital platform, let’s say a video game, is generating revenue from its users by creating these really cool add-ons that people want to buy, but at the same time they’re guessing what their users want. The opportunity here for brands is, right away you can give users relatable content that they already enjoy in real life.”

“People spend their money where they spend their time, and more and more people are spending their time in digital ecosystems, but brands aren’t fully capitalizing on this yet,” said David Uy, co-founder and CEO of BLMP Licensing Marketplace, a new platform that helps facilitate licensing partnerships between brands and digital publishers. “The digital platform, let’s say a video game, is generating revenue from its users by creating these really cool add-ons that people want to buy, but at the same time they’re guessing what their users want. The opportunity here for brands is, right away you can give users relatable content that they already enjoy in real life.”

David’s company, BLMP Licensing Marketplace, aims to make it easier for brands and digital platforms to connect and tap into this opportunity. BLMP Licensing Marketplace not only allows participating brands and platforms to strike deals for virtual goods, but it also allows brands to easily follow their IP through the process from product creation to sale and even re-sale. (Yes, there’s a whole market out there for peer-to-peer trading and selling of “second hand” virtual goods, although we won’t get into that here.)

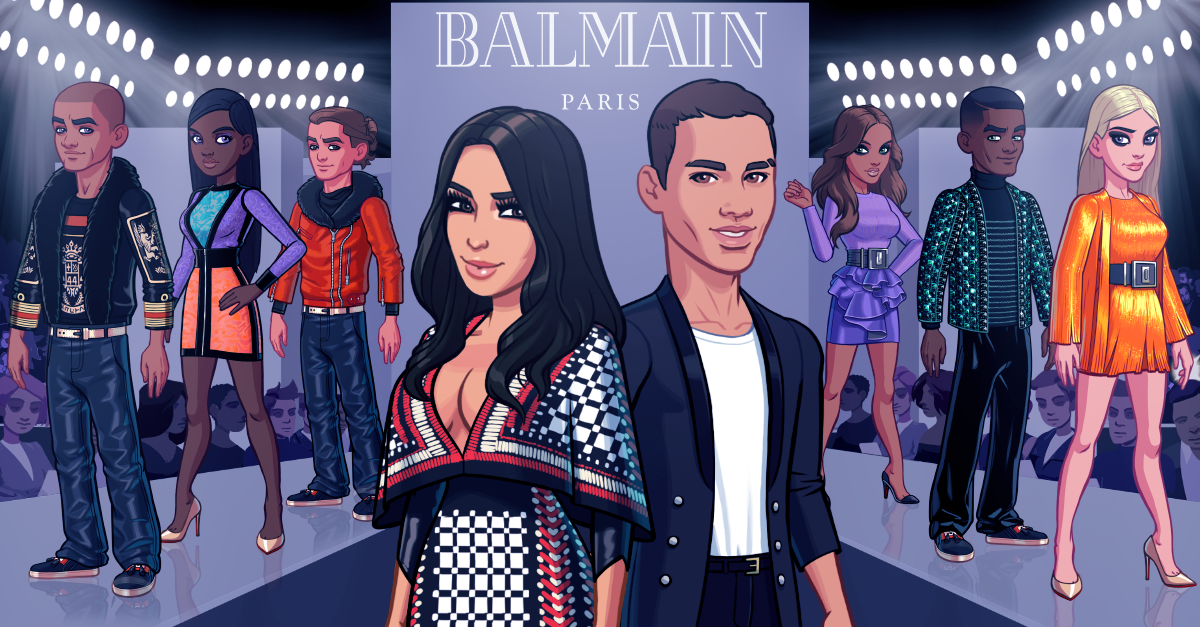

To understand how tremendously profitable branded virtual products can be, one need look no further than modern media maven Kim Kardashian. Her mobile game, “Kim Kardashian: Hollywood,” has raked in hundreds of millions of dollars since its 2014 launch, according to the game’s developer Glu Mobile. And since the game is free-to-play, that money is coming almost exclusively from the sale of virtual luxury goods within the app, things like private planes and high-end clothing and accessories.

“The Kim Kardashian game made close to $75 million in its first year alone selling virtual goods to teenagers who wanted to emulate Kim’s celebrity lifestyle,” said David. “It got to the point that the teenagers were so engaged, that the luxury brands themselves were actually creating custom pieces for her game.”

“The Kim Kardashian game made close to $75 million in its first year alone selling virtual goods to teenagers who wanted to emulate Kim’s celebrity lifestyle,” said David. “It got to the point that the teenagers were so engaged, that the luxury brands themselves were actually creating custom pieces for her game.”

Among the real-world luxury brands who signed on to create exclusive virtual merchandise for the game are Chanel, Karl Lagerfeld and Balmain designer Olivier Rousteing.

But Why?

For some, the idea of spending real money on products that don’t technically exist can be a bit difficult to understand, but according to David it makes perfect sense.

“People buy things online for the same reason they buy things offline–status, differentiation, identity, membership,” he says.

And this is why the virtual goods space offers so much opportunity to brands. If someone is a loyal consumer of your brand in the real world, there’s no reason that loyalty won’t extend into the digital world as well.

Take a Marvel fan for example. He’s already willing to spend money on clothes, toys and other products featuring his favorite superhero, so it’s not such a stretch to imagine that he would also buy an Iron Man-themed car to drive in his favorite racing app. His motivations for the digital purchase won’t be that different from his reasons for buying a t-shirt or action figure in the real world.

This is especially true in multi-player universes like “CS:GO” or “Kim Kardashian: Hollywood” where players interact and build relationships with other people–just like in any other social setting, status and identity, often expressed through things like clothing, are crucial to these interactions.

The Brand Advantage

It will come as no surprise that, as with most new trends, younger consumers are driving the growth of virtual goods sales. Additionally, the market is much more mature in other regions of the world than it is in North America at the moment, particularly in Asia.

“In North America it’s not as common yet for people to buy stuff in games, but in Asia it’s very normal, it’s like buying Starbucks,” says David.

Entering the virtual goods marketplace provides a new avenue for brands to reach these two highly desirable demographics and can also present a relatively low-risk way to test out new markets.

And the fact that the products don’t actually exist is an advantage in and of itself. This merchandise isn’t restricted by the physical limitations of the real world. Gone are the time and financial constraints of product development and supply chain concerns. In many cases the platform or developer will do the work of creating the virtual good themselves, all the brand has to do is approve.

That’s because, for these digital platforms, virtual goods have become an essential way to not only make money, but to introduce new content that maintains engagement among users.

“These digital ecosystems, they rise and fall,” explains David. “There was MySpace, and then it goes obsolete, now there’s Facebook, Instagram, etcetera. You might have the hottest game of the year right now, but there will be another one next year. These companies have to spend a tremendous amount of time keeping their users, because those users are extremely valuable to them. They also need to find ways to monetize. Branded virtual content creates excitement among users and has the added bonus of generating revenue for both the platform and the brand.”

In fact, virtual goods can become a viable alternative to traditional digital advertising for many brands. “It’s not just about the sales of the virtual goods. The virtual good is advertising in and of itself. Just the fact that it’s in the store of a platform is a kind of advertising,” said David.

Connecting the Dots

One problem with the virtual goods marketplace that has been a barrier to entry for many brands has been the mechanics of the deal itself.

To illustrate the problem, David recounts a conversation with his mentor Henk Rogers, the creator of “Tetris,” who now serves as a BLMP Licensing Marketplace advisor.

“When Henk got into the gaming business, you sold disks or cartridges, those were physical goods, easy to track,” said David. “Then it evolved into downloads, so okay, we track the downloads. But now, based on the freemium economy that is driving everything across social networks and gaming, everyone is playing for free, and you have to track all these micro-transactions within each game. How do you even know that your records are right? It requires a lot of effort and trust. What I told him is, we can solve this problem using blockchain.”

Blockchain is the decentralized accounting technology that was originally developed for cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. This technology has now come into its own and is being recognized for its many other potential applications. This includes the safe, reliable and secure tracking of digital transactions, and it is BLMP Licensing Marketplace’s secret weapon.

“Blockchain is fully transparent, and in using it to develop our network, we create trust in a trustless system,” he says. “So now all of a sudden if Henk is making a deal in a country overseas, he can actually see all the micro-transactions as they happen, and it’s all secured cryptographically. There’s no way to go back and fraudulently change the data, so consumer transactions involving your intellectual property can be tracked and traced without any fear of tampering. That’s revolutionary, that’s never been done before.”